We found ourselves together in a small room, an assortment of technology experts, musicians and fascinated observers, all moving around each other, the air abuzz with the industry unfolding at the tables around us. We were in the basement of London’s Royal Festival Hall, brought together to see the fruits of the DM Lab Challenge – an initiative from Drake Music, supported by the British Council, calling for instrument makers to bring in their ideas and working models for accessible instruments.

Just outside our basement room, Festival Hall staff were busy preparing an installation amidst cans of paint and assorted power tools. It gave the whole area a feel of being “under construction”, a fitting backdrop for this Hackathon event as, inside the room, our gang involved with the DM Lab Challenge were busily perfecting their instruments. International colleagues, invited by the British Council from countries in North Africa and Asia, mingled with the makers, asking questions, trying out the models.

Leah Zakss, Programme Manager for the British Council’s Music team in London, explains: “It was amazing to see what entrants had produced in such a short period of time, and refreshing to be connected to a whole new network of people around the UK working in the field of AMT [assistive music technology]. I know that our international colleagues who visited were amazed at the innovation on display … we had a lot of fun and learned so much.”

Drake Music are a charity with offices in Bristol, Manchester and London that, for 20 years, have forged partnerships and explored technology designed to break down barriers to music-making for musicians with special educational needs and disability (SEN/D). They’ve put on many of these Hackathon events over the years and see it as a perfect way to bring people together and share their ideas and try them out in an environment that allows for mistakes and trial and error. “I think we need to have a much broader range of choice when it comes to accessible music making, to encompass multiple genres as well as physical barriers,” said Gawain Hewitt, Head of R&D for Drake Music. In terms of barriers to disabled musicians, Drake Music can provide some solutions by developing instruments that cater for the musician’s needs.

The DM Lab Challenge introduced us to a number of new ideas and, while some of the instruments on show were very much in their infancy, we also saw some more established designs from Drake, chiefly their Kellycaster guitar, designed with the musician John Kelly, and the MiMu Gloves, made famous by Imogen Heap and here demonstrated by Kris Haplin. We also saw an accessible conductor’s baton, demonstrated by James Rose.

Above: Discover three musicians' stories about accessible music technology

Products like the MiMu Gloves show us that, far from being a niche of instrument design purely for disabled musicians, this sort of music technology should appeal to all musicians irrespective of their physical capabilities. I spoke to Zen, co-inventor of the Beard Organ: “I believe good design is inclusive design,” he said. “Versatility and forethought allows the product to be used by different people in different ways. A good product enables the user to do something they couldn't do before.”

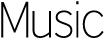

Elsewhere in the room, Dave Darch’s Fist Piano showed that music technology needn’t be expensive either. This charming instrument is made of clothes pegs, scrap wood and a lever arch file; it’s capable of triggering audio with very low latency and could be produced for £15. “My aim is to produce an engaging musical instrument that can be built very cheaply and modified by moderately skilled makers around the world to allow access to musical expression for people who lack the fine motor control and/or strength required to play most musical instruments,” explained Dave.

Above: Dave Darch's Fist Piano

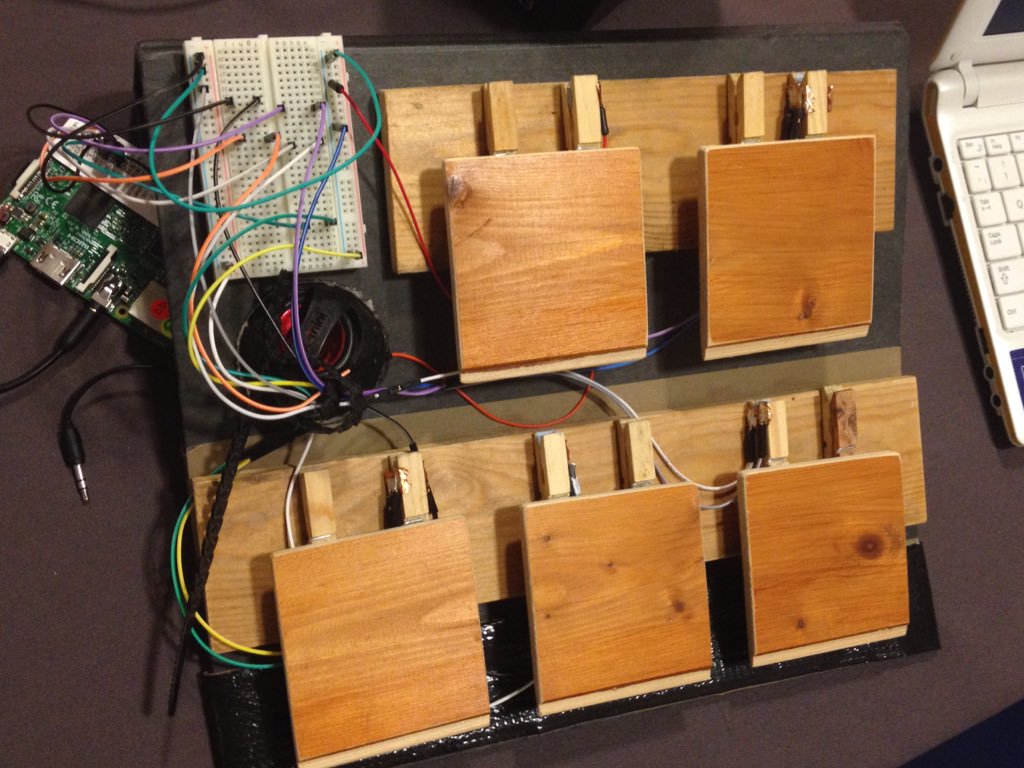

There were other instruments in the room with international appeal too. “I can promise you, it won’t give you an electric shock,” whispered Charles Matthews, as he strapped the virtual bow of his electronic Rebab across the arm of one of our guests from Egypt. Ordinarily, the Rebab is a Javanese instrument played as part of a gamelan ensemble. The physicality required to bow the instrument means it is not possible to play if you are a musician that struggles with that sort of movement or you don’t have the necessary muscle strength to make a forceful bowing action. Charles’ solution effectively replaces the bow by using muscle sensors attached to the arm – a leg or even the musician’s face would work too – which pick up on the body’s natural electrical signals that are passed through the muscle when it twitches. The sensor can then interpret this information in musical form, and “there's no need for external equipment or computer,” explained Charles “as the instrument runs on the Bela platform with its own speaker mounted.” Incredibly, the player can change the volume of notes, add vibrato and perform glissandi (sliding between notes) all from the smallest of muscle movements. “The muscle sensor can also be swapped for a flex sensor that works with fingers or arm movement,” offered Charles. “I've attempted to make it modular in order to fit a variety of access needs and preferences. It's also less reliant on fine motor skills than the traditional instrument, so could be used as a learning tool.”

As the original rebab is part of a family of instruments not usually tuned to Western pitches, Charles’ design certainly seems to take accessible music technology into new territories, literally: “The instrument can be retuned to match different gamelan, with an option for equal temperament.”

Above: Charles Matthews' accessible rebab

It was also intriguing to hear the instrument makers talk about considerations beyond the technology too. Billy Payne’s Capacitive Touch Violin – or “Tiddle” as he likes to call it – uses an old, discarded violin body connected to a computer to produce tones with only one hand required. It’s also possible to use a number of the same expressive techniques familiar to regular violin players. However, when I spoke to him, it was clear that the look of the instrument was almost as important as the functionality. He was concerned the LED lights down the neck might be a bit gauche if this instrument was featured in a classical concert with the house lights off. It was a level of detail I had not expected to encounter. To me, seeing an ingenious and strikingly modern bit of technology which looked like a “proper instrument” was fascinating: this instrument is, predominantly, not made from modern plastic but from wood and copper that will age over time. If I were a violinist myself, I could really bond with an instrument like that. After all, the reason many of us take up instruments and stick with them is because there is something about the instrument we connect with, something that speaks to us and demands that we play. What good is an instrument that doesn’t make you want to do that?

There is certainly something about Hugh Aynsley’s Stretchi in this regard. “The instrument itself is made from five rubber strings to give the tactile feel of an acoustic instrument but with the possibilities of electronic sounds and control,” explained Hugh. “The strings are velocity sensitive to give more control and therefore more expressivity. Other functions include holding the notes for longer durations and pitch bending the note, all from touching the string … One user of the instrument, who can’t communicate verbally, enjoyed controlling the choir samples and another user also enjoyed the choir sample and sung along.” This element of control and flexibility granted to the musician is key. “[The] music technology you use shapes the outcome quite profoundly, so to be in control of the tools themselves is a very powerful thing,” concurred Gawain Hewitt.

Ultimately, removing the barriers to music making is the name of the game and although the DM Lab Challenge focussed mostly on physical barriers, it certainly left me thinking that disabled and able-bodied musicians need help from time to time to either get started or keep on going with their music. “People need help to find their path,” said Gawain, “in fact, I think we are all looking for the way to progress.”

– Stephen Bloomfield

- Sign up here for the Disability Arts International Newsletter

- Visit the Disability Arts International website here

- Find out more about Drake Music here

- Find out more about Charles Matthew's Gamelan project

- Read about James Rose’s new project with BSO and an ensemble of disabled musicians