We’re very excited about our upcoming Film, Archive and Music Lab week (FAMLAB) with British Film Institute, PRS for Music Foundation and HOME in Manchester. FAMLAB brings together 16 musicians, composers and film makers from around the UK and East Asia. On day one, journalist, academic and curator Ian Haydn Smith will set the scene with a whistle-stop journey through some of his favourite film music moments. Here he writes about the interplay between music and film in a piece commissioned by the British Council.

A Perfect Balance

Don’t you wonder sometimes 'bout sound and vision

– David Bowie

Cinema is comprised, in equal parts, of sound and image, even if the latter seems to take precedence. And sound itself has two components: a disparate range of audio tracks that include dialogue, effects and textures that add layers of audio to a scene, and music. Music is an integral part of the cinematic experience, even if it is sometimes most notable by its absence.

In the era before synchronous sound – after all, cinema was never ‘silent’ – music played a significant role. Played live, it welcomed audiences into a nascent world of flickering images, before adopting an increasingly complex role within a film’s soundtrack. It was there to add a spark to a scene or underpin an emotional state. The choice of music might differ wherever a film played in those days, depending on the skill or mood of the accompanist. But as films became more refined, the soundtrack was used to embellish upon, or contrast with, the images appearing on a screen. Sometimes this could be quite abstract. For instance, Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí’s surrealist classic Un Chien Andalou (The Andalusian Dog, 1929) employed Richard Wagner's "Liebestod" from his opera Tristan und Isolde as well as scratched recordings of two Argentinian tangos more as a counterpoint than to complement the dream-like imagery, daring us to draw associations where there may be none.

Context

If you removed the score, Saul Bass’ extraordinary opening credits to Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) appear like avant-garde animation: a grey canvass divided by a series of horizontal and vertical lines, varying in speed as they journey across the screen and are broken up by text. Add Bernard Hermann’s jolting, staccato composition and the lines now slice the screen violently. They herald the arrival of something different, something new. And like any great horror score, the music is the first thing to unsettle us. Scare us, even.

As the filmmaker Peter Strickland has pointed out, the worlds of the European horror fan and anyone with a penchant for contemporary avant- garde classical music aren’t so different. Someone attending a Ligeti or Penderecki concert may balk at the idea of watching one of the classic Italian horror genre Giallo movies of the 1970s – and vice versa – but horror in cinema has often been accompanied, or inspired by, the kind of experimental, atonal music that has graced the world’s greatest concert halls. Strickland employs this relationship to brilliant effect with his stunning deconstruction of the making of an Italian horror film, Berberian Sound Studio (2012), which features a score by the experimental band Broadcast.

A film score offers context to a film. It can signify a genre, alert us to a shift in the narrative and, by employing a Wagnerian leitmotif – as evinced in the more populist films of Steven Spielberg and the better entries in the Star Wars series – it can embellish upon a character. It can also play with expectations. Ennio Morricone’s scores for Sergio Leone’s Dollar trilogy (1964-66) and Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) offer up recognisable Western motifs whilst also employing atypical instrumentation that informs us we’re some distance from the conventional representation of the American West.

Drama/Suspense

Hitchcock understood music’s potential, constantly pushing the relationship between sound and image. The thriller, a genre he made his own, can employ music to build suspense. And not just through a non-diegetic score. In one of the most famous sequences of his 1934 version of The Man Who Knew Too Much, the assassination of a foreign diplomat is planned to take place during a classical performance at the Royal Albert Hall. The heroine is in the audience, desperate to find a way to prevent what is about to happen, but fearful for the safety of her kidnapped daughter. Like her, we know when the shooting will take place – in the climactic moments of the composition, as the percussionist clashes a pair of cymbals. We sit, like the woman, with our heart in our mouth, in anticipation of the moment the cymbals appear. All the while, the music heightens our sense of suspense. It also gives the sequence a specific pace.

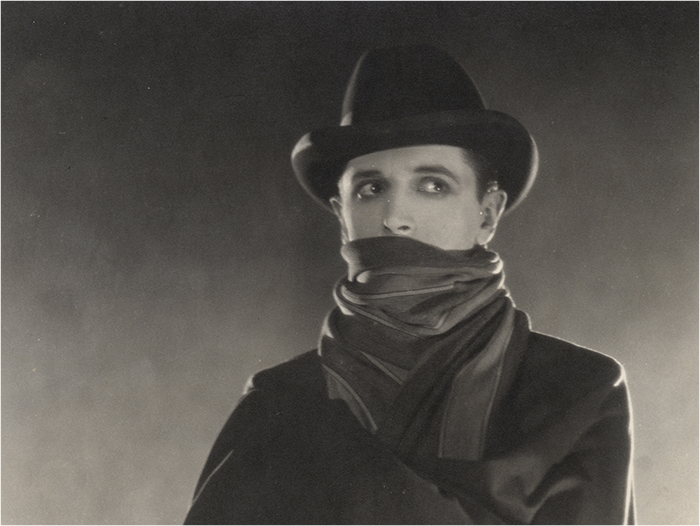

From Hitchcock's The Lodger. Photo credit: BFI

Rhythm

But Hitchcock didn’t always require music to create a beat. Cut to 25 years later and one of Hitchcock’s most celebrated scenes – the crop duster sequence in North by Northwest (1959). A bus arrives at a deserted crossroads in the middle of America. Cary Grant disembarks, expecting to meet the mysterious man he has been mistaken for and as a result finds his life under threat. A plane flies in the distance. A man is dropped off at the crossroads. He’s not who Grant character has been waiting for, but he remarks that the crop duster is dusting a fallow field. No sooner has the man departed on another bus than the plane makes a beeline for Grant, first flying low and sending him diving for the ground, then firing at him and crop dusting him with its cargo, before crashing into a fuel truck and exploding. It is only then that Bernard Hermann’s score enters the scene, over 10 minutes after it began. And yet the film has its own musicality. Hitchcock’s approach to editing creates a rhythm that drives the scene forward, the shots gradually reducing in length in order to quicken our pulse. The use of the music at the end is a release – the pressure valve finally allowing us to breathe again.

Composers create rhythms in ways that suit their style of the demands of a narrative. Philip Glass employs arpeggios in his film scores – from the frantic escape of the Dalai Llama in Martin Scorsese’s Kundun (1997) to the ebb and flow of life, as represented by the river, in Stephen Daldry’s The Hours (2002) – while Steven Price creates a wall of sound, a sense of impending danger growing with each passing second, in Gravity (2013). Here, music sets the rhythm as much as it does the film’s tone.

Emotion

Memory can prompt an emotional response in us. A recognisable song carries its own emotional weight. It can be fabricated – the new songs in Dirty Dancing (1987) are as charged as the classics they appear alongside because of the import they’re given within the narrative. Or a director and their music supervisor might incorporate a new meaning with a familiar track. Quentin Tarantino’s entire cinematic output has profited from the recycling of familiar or cinematically significant songs, as well as excerpts from other scores. It is only 25 years into his career that he finally features an original score in one of his films, for The Hateful Eight (2015). Even then, Ennio Morricone comes with more cultural baggage than the average composer.

Wong Kar-wai has also revealed a penchant cultural recycling. In Chungking Express (1994), he uses The Mamas and the Papas’ "California Dreamin’" to tell us about character, to hint at the route a narrative will take and, ultimately, to infuse an upbeat, exuberant pop song with an air of melancholy, as it comes to represent an opportunity missed – a love affair that never happened. He takes appropriation further in the gorgeous In the Mood for Love (2000). Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung’s theme, played as their characters occasionally encounter each other on the streets of 1950s Hong Kong, was originally composed by Umebayashi Shigeru for Japanese director Suzuki Seijun’s 1991 drama Yumeiji. Not that you would notice, as it perfectly encapsulates the attraction between the two characters.

Nitin Sawhney’s soundtrack for Hitchcock’s The Lodger (1927), one of the original compositions commissioned for the BFI’s Hitchcock 9 restoration project, which the British Council has now toured the world, employs both an original score and songs. Soweto Kinch’s jazz score to The Ring (1927) and Schlomo’s radical score for the human voice for Downhill (1927) – the first such score in cinema history – as well as the more ‘conventional’ scores for the remaining Hitchcock restorations, underpin the nature of film composition, creating something fresh that embellishes on a film’s themes and character development, draws out tone and atmosphere, and engages us on an emotional level. Richly evocative or sparse, a film’s score or soundtrack can inform as much as it engages, creating another layer of dialogue between a film and its audience.

– Ian Haydn Smith

Ian Haydn Smith was editor of the International Film Guide and since 2011 has been the editor of Curzon Magazine. He has contributed to numerous publications in the UK and internationally and regularly represents the British Council at film and arts events around the globe. He co-wrote New British Cinema (2015) with Jason Wood, Artistic Director of Film at HOME, Manchester.

You can read more about the FAMLAB project here and follow #FAMLAB on Twitter throughout the week (starts 29th February 2016). Try our film and music playlist here.